As graduates prepare to enter the corporate world as managers, analysts, or entrepreneurs, one financial skill consistently separates average decision-makers from exceptional ones: the ability to understand and interpret the value of a business. Company valuation is not merely an academic exercise or a tool used by investment bankers on Wall Street. It is a practical framework that allows managers to assess strategic choices, allocate resources efficiently, and judge whether a company is creating or destroying value over time.

At the core of modern valuation lies the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) approach, which is built on two fundamental concepts: Free Cash Flow (FCF) and the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). Together, these concepts allow managers to estimate a company’s intrinsic value based on its future cash-generating potential rather than short-term accounting profits or market speculation.

Understanding Free Cash Flow, WACC, and Valuation

Company valuation is the process of estimating the economic worth of a business by forecasting the cash it will generate in the future and discounting those cash flows back to the present. Among various valuation methods, the Free Cash Flow approach is widely regarded as the most comprehensive because it focuses on actual cash available to investors after operating and reinvestment needs are met.

Free Cash Flow represents the cash generated by a company’s core operations that is available to both equity holders and debt providers. Unlike net income, FCF removes accounting distortions and focuses on real economic performance. It answers a critical managerial question: how much cash can the business distribute without harming its ability to operate and grow?

WACC, or Weighted Average Cost of Capital, represents the required return expected by all providers of capital. It reflects the firm’s risk profile and financing structure. In valuation, WACC is used as the discount rate because it captures the opportunity cost of investing in the business rather than in alternative investments with similar risk.

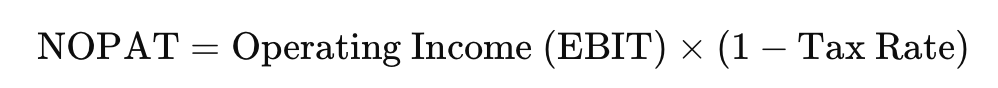

Step 1: Calculating Net Operating Profit After Tax (NOPAT)

The valuation process begins with the calculation of Net Operating Profit After Tax (NOPAT). NOPAT measures the profitability of a firm’s core operations after taxes, while ignoring how the business is financed. This makes it an ideal starting point for valuation because it isolates operating performance from capital structure decisions.

The formula for NOPAT is:

By focusing on EBIT rather than net income, managers remove the effects of interest expenses and other financing items. NOPAT reflects what the company would earn if it were financed entirely with equity, allowing for cleaner comparison across firms and industries.

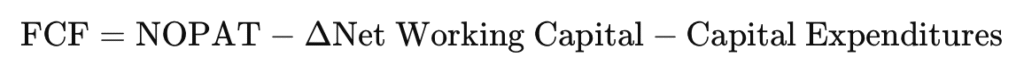

Step 2: Incorporating Net Working Capital and Long-Term Assets

While NOPAT measures operating profitability, it does not reflect how much cash is actually available to investors. To arrive at Free Cash Flow, managers must account for the reinvestments required to sustain and grow operations. These reinvestments primarily occur in net working capital and long-term assets.

Net working capital includes operating current assets such as inventory and receivables, minus operating current liabilities such as payables. An increase in net working capital consumes cash, while a decrease releases cash back to the firm. Similarly, investments in long-term assets—often reflected as capital expenditures—represent cash outflows required to maintain productive capacity.

Free Cash Flow is calculated as:

This step is crucial because high profitability does not always translate into high value. Firms that require heavy reinvestment may generate impressive earnings but little free cash, ultimately limiting shareholder value.

Step 3: Accounting for Growth

Growth is a powerful driver of value, but it must be approached carefully. Managers must forecast how sales, operating margins, and reinvestment needs will evolve over time. Growth assumptions should be economically justified and consistent with industry conditions, competitive advantage, and reinvestment capacity.

Importantly, growth affects Free Cash Flow in two ways. First, higher growth often increases future operating profits. Second, growth usually requires additional investment in working capital and fixed assets. Sustainable growth, therefore, depends on a firm’s ability to generate returns above its cost of capital.

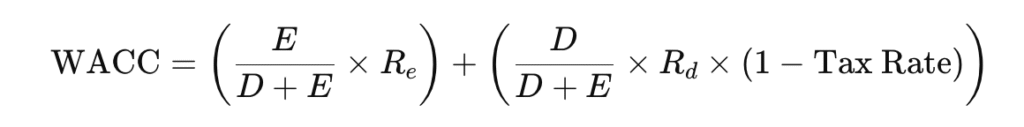

Step 4: Calculating the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC)

Once future Free Cash Flows are estimated, they must be discounted using the company’s Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). WACC represents the average rate of return that the company is required to pay to all its capital providers—both equity investors and debt holders—for the risk they bear by investing in the business. It serves as the discount rate in valuation because it reflects the opportunity cost of capital and the overall risk profile of the firm.

The formula for WACC is:

In this formula,

E represents the market value of equity,

D represents the market value of debt,

(R_e) is the cost of equity,

(R_d) is the cost of debt, and

(D + E) represents the total market value of the firm’s capital.

The tax rate is used to adjust the cost of debt because interest payments are tax-deductible, creating a tax shield.

From a managerial perspective, WACC acts as a benchmark for value creation. If a project or strategy generates returns above WACC, it adds value to the firm; if it falls below WACC, it destroys value. Understanding WACC allows managers to make better capital budgeting decisions, evaluate strategic investments, and align business performance with investor expectations.

Step 5: Determining the Valuation Period

Managers typically forecast Free Cash Flows over an explicit valuation period of five to ten years. This period captures the time during which the firm is expected to experience measurable changes in growth, profitability, or competitive position. Forecasts during this phase should be detailed and grounded in operational assumptions rather than purely financial targets.

Step 6: Discounting Free Cash Flows to Present Value

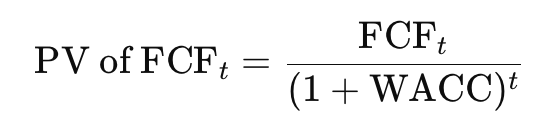

Each year’s Free Cash Flow is discounted back to the present using WACC:

This process reflects the time value of money and risk. Cash flows expected further in the future are worth less today due to uncertainty and opportunity cost.

Step 7: Calculating the Horizon Value

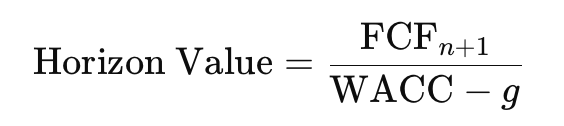

Because companies are assumed to continue operating beyond the explicit forecast period, managers calculate a horizon value, also known as terminal value. This value captures all cash flows beyond the final forecast year under a stable growth assumption.

The horizon value is discounted back to the present and often represents a substantial portion of the firm’s total value, highlighting the importance of realistic long-term assumptions.

Why Valuation Skills Matter for Future Managers

For managers, valuation is more than a financial model—it is a decision-making lens. It helps evaluate investments, guide strategic initiatives, assess mergers and acquisitions, and align operational choices with long-term value creation. Graduates who master valuation can link everyday managerial decisions to shareholder value, making them more effective and credible leaders in the modern business environment.